- News

- A year in architecture - 2018 newsmakers (Part 2 of 3)

A year in architecture - 2018 newsmakers (Part 2 of 3)

A year in architecture – 2018 newsmakers (Part 2 of 3)

by M. James Ward

The 2018 calendar is drawing to a close and looking back there were a number of key newsmakers clearly providing a significant impact on the architectural side of things. In some cases the headliners of 2018 will carry forward into 2019. The golf world is quickly evolving on a range of fronts and the new year ahead will certainly carry both opportunities and challenges.

Golf ball distance debate – talk yes – action no

When politicians are loath to act on tough issues they quickly employ a common tactic passed down over the ages – kick the can down the road and let someone else handle it. That manner of leadership (dare it be called such a thing) is what the USGA and R&A have decided to do despite clear evidence that on the world's highest golf stage – the PGA Tour – gains are clearly accelerating.

Unlike the "slow creep" which was how the USGA defined gains in past years, the average jumped from 292.1 yards to 296.1 for the 2017-2018 season, four yards in just one year. Just one year prior, the gains were 2.1 yards.

Given this reality the USGA & R&A created an 18-month comprehensive study aptly named the “Distance Insights Project”. That study will encompass all the key professional tours, including everyday golfers, via online and telephone surveys.

No organization or reputable individual has refuted that the data is not true. The primary objective of such organizations as the USGA and R&A is to enact rules concerning golf equipment which keep the game in some sort of balance. That balance is no longer in question. The more meaningful question is what purposeful actions, if any, will the USGA & R&A make?

Some outside the two rule making groups have lobbied for bifurcation – one set of equipment rules applying to those at the highest levels of professional golf and another for those playing the game recreationally. The USGA has clearly stated its opposition to that possibility. Ditto the R&A.

There is also increasing skepticism that the two rule making bodies will ever act decisively on this topic for fear of litigation from ball producing companies. Years ago in the 1980s, when a controversy emerged over the depth and dimension of square grooves for irons, the late Karsten Solheim (the founder of PING) sued the PGA Tour, arguing the methodology used was flawed. Eventually, Solheim prevailed via an out-of-court settlement to grandfather the clubs in question. Only after the brouhaha had settled did the USGA act to ban such grooves. When did that happen? Try 2010. Not exactly, a decision taken at the speed of light. Keep in mind, that this is the same USGA that failed to outlaw metal woods during the mid-1980s when such clubs clearly had a major impact on the spike of distance when compared to traditional woods.

Throwing down the gauntlet against future ball increases will be a very problematic stance for the rule making bodies. Both are intent on acting in a joint capacity and it's been known that the R&A, more than USGA, is not exactly thrilled by the idea of fighting such an issue that potentially could involve major lawsuits which could siphon large sums of money from their respective organizations.

Various architects and even top players such as Jack Nicklaus have called for action numerous times over the years. Courses have been unduly lengthened with such noteworthy examples being The Old Course at St Andrews and Augusta National, to name just two of the most prominent.

There's little question that at the very, very top of professional golf the players are more athletic – bigger and stronger is becoming more and more the norm. Power is quickly taking over as the prerequisite attribute in order to establish dominance. Winning scores are increasingly going lower and without some sort of meaningful brake, the end game will no doubt be a de facto split as wide as the Grand Canyon between the very top and the rest of the game's players. Can a resolution be negotiated with all the key parties? From the ball manufacturers side there's little need or desire to do so. Given that likelihood, will the ruling bodies summon the courage to do the heavy lift on their own? If past actions are any guide don't count on it.

Pete Dye says goodbye

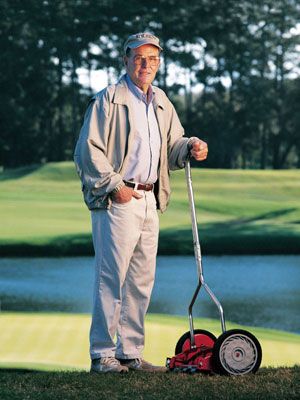

In the second half of the 20th century, arguably, there was no more influential figure in golf course design than Pete Dye. The 92-year-old native from Ohio who has lived the bulk of his life in Indiana will turn 93 by month's end. Sad to say but Dye has withdrawn from any future projects – the last coming with The Links at Perry Cabin in St. Michael's MD, which had a soft opening in 2018.

Dye is in the grips of dementia, but his presence in golf is clearly in the same vein with such icons as Donald Ross, A.W. Tillinghast and Alister MacKenzie, to name just a few. Dye brought back into focus the classical period of architecture that germinated in the UK and Ireland and then early on in America during the heyday of the 1920s and 1930s during the “Golden Age” of architecture.

The ebullient Dye changed the focus of golf course design that went far beyond his insertion of his trademark railroad ties. The need for shot-making was clearly focused upon, and his early success with Harbour Town in South Carolina in the mid-1960s was cemented when the likes of Arnold Palmer won the inaugural event with Johnny Miller, Jack Nicklaus and other players of note following in the years ahead. Dye demonstrated a clear counterpoint to the muscular larger-than-life style practiced by Robert Trent Jones Sr., who was the game's premier architect during Dye's initial career start.

The momentum for Dye continued when opening the famed Teeth of the Dog course at Casa de Campo in the Dominican Republic in 1971. In that location Dye masterfully weaved holes near to the Atlantic Ocean on both nines and showed clearly how resort golf could be the main headliner.

Dye gained increasing visibility – and a bit of wrath – from the world's best players in creating "visual horror" in order to rattle them. The opening of TPC Sawgrass in the autumn of 1980 marked a critical high water mark. Dye gained major fanfare with the final three holes at the course, but the clear star was the green encircled by water par-3 17th. This short hole of just 132 yards has been a deal breaker for many professionals over the years. While not considered an "official" major, the weight of The Players Championship is clearly prized by professionals for the stature it now conveys.

At roughly the same time, Dye added another gem to his career with the opening of The Ocean Course at Kiawah near Charleston, SC. When the Ryder Cup Matches for 1991 were announced the course had not even been completed. The close proximity to the Atlantic Ocean meant a steady dosage of shifting high winds and scorecard punishment for even the finest players in the game. The American victory was not assured until Bernhard Langer's missed six-foot putt at the final hole.

Dye was also involved in creating different venues for the PGA Championship. Locations such as Oak Tree, Crooked Stick and Whistling Straits three times – the Wisconsin club will next host the Ryder Cup Matches in 2020.

The success of Dye is not a singular element by any means. At his side since 1950 has been his wife, Alice. Pete will be the first to admit the deep influence his wife has continually provided. The fingerprints Dye first cast have been mirrored by other architects who cut their teeth when starting their careers. They include the likes of Jack Nicklaus who consulted with Dye on Harbour Town, and years later with the likes of Tom Doak, Bill Coore, Tim Liddy, John Harbottle, Bobby Weed, Rod Whitman, Jim Urbina and Lee Schmidt, to mention just a few.

In short – the Dye legacy will live on no matter what.

Alternative golfing options emerging

Golf is facing a dilemma. Course closures have been outdistancing openings in America, Canada and the UK since the Great Recession hit in 2008. In other areas, such as Asia, golf is showing new development, but many of those specific openings are largely for the enjoyment of those with the deepest of pockets.

Attempts to reach out to a newer, younger audience – the millennials – are developing with a range of different approaches. Among the leading efforts is Topgolf. Originating in the UK and then blossoming with new ownership in America, the company has over 50 locations worldwide, employing over 15,000 and serving approximately 13 million guests. Roughly 70% of the people who visit Topgolf have never before held a golf club.

The concept is simple – provide a social gathering place where food and drink is served and link a golf connection as the entertainment vehicle. Topgolf uses the driving range formula in a modified manner, creating various games in which people can compete with one another, or simply enjoy the platform of golf for some friendly fun.

Topgolf is rapidly expanding with numerous sites throughout America and internationally planned for 2019. There's even speculation of a future site in Florida’s West Palm Beach, which will have an actual golf course located next to a generic facility.

The issue meriting additional study is whether Topgolf can actually serve as a springboard, taking those who were never exposed to golf and move them towards playing the game through conventional means as their main recreational sport. Thus far, there's no clear study that can demonstrate that connection. Topgolf has engaged Callaway as their main equipment provider and lessons are offered for those intent to do more than just share a social connection. The success of Topgolf has spurred another competitor called Drive Shack, which is patterned in a similar fashion. How much more space is there for the market to develop? Clearly, the companies believe there's much more room on the growth side.

There are also movements to shorten the golf experience with various routings that include a number of holes less than 18. Some previous 18-hole courses have opted to shut down a portion of their facilities for other development while keeping 9-hole courses active. There are some facilities simply charging amounts based on the actual total number of holes you play. There are also attempts to resurrect "executive style" courses where the total length of the holes is much shorter than many courses. At Pinehurst the desire to include some form of alternative 18-hole rounds was the genesis for the creation of The Cradle – a 9-hole short course immediately near to the main clubhouse. The handiwork of Gil Hanse allows for quick entertaining rounds for all ages to enjoy. Other traditional courses have also gone ahead with plans to add various adjoining short courses to keep their members and guests engaged. The success of the 13-hole short course called Brandon Preserve by Ben Crenshaw and Bill Coore at Bandon Dunes in Oregon is another example of this type.

Outside of pure golf experiences there have been efforts via such games as Footgolf – where players kick an actual soccer ball on a real golf course to a prepared hole where play concludes. Some have wondered if such an activity will ever create a pathway where people move towards traditional golf. The same situation applies with Frisbee Golf where players throw a frisbee to a predetermined target placed throughout a golf course's routing.

Golf’s main handicap for the newest generation of players evolves around the time to play, the cost of the equipment and the learning curve to fully enjoy the sport. A number of the remedies have only come in recent times, since much of the industry was under the false impression that all was well with the sport and that nothing needed happen. The Great Recession ended that fallacy in a big way.

Alternative golf may be frowned upon by a certain percentage of died in the wool traditionalists, but it's clear that without different avenues to engage new players the very real possibility exists that golf could retreat back to the days when only those with the heftiest of bank accounts enjoy the game. That scenario is by no means out of the question at this moment. Creating variations of the golf model is an exploration of various concepts, which bodes well. The question in 2019 is just how much more momentum can be generated, because as each day goes by, the age of the Baby Boomers – the biggest grouping of core golfers now – gets older and replacements will be needed for the sport to continue to thrive in the years ahead.